Kanika M., 43, grew up thinking that therapy was only for privileged white people. As a Black person, coming from a Black family, she was taught that you don't "air your laundry in the streets." "It wasn't something that was encouraged or thought of as necessary unless you had a mental illness," she says. "Instead, we were taught to just pray about it, and God will provide an answer."

As she got older, Kanika says she became more curious about therapy. But for a number of years, her reservations about the stigma surrounding it kept her away, she adds. "I worried about not only other people's perception of me — what would people think? — but also my own perception of myself," she says. "I worried about what it meant about me and who I was. Why couldn't I handle this?"

Kanika was raised by her mother and three aunts, who she describes as "four strong, independent women." Because of that, she says she felt that not having an answer or not being able to deal with something on her own never felt like an option. "Instead of seeking support for myself, I overworked, overly dedicated myself to helping others, and overpoured myself into my family."

This thought process isn’t uncommon. It resides in the idea that Black women are not supposed to recognize pain, says Aeva Gaymon-Doomes, M.D., a licensed psychiatrist in private practice in Washington, D.C. “We are told by society that we are supposed to embrace being magical beings that are Teflon, and are resistant to being ignored, abused, maligned, exploited, and somehow… find pride in being called a superwoman.” (See: Why We Really Need to Stop Calling People “Superwomxn”)

That title, though, is not exactly a badge of honor. According to a 2010 study titled “Superwoman Schema: African American Women’s Views on Stress, Strength, and Health,” this “Superwoman” persona that so many Black women adopt locks them in a box, forcing them to manifest strength, suppress emotions, possess the determination to succeed (despite limited resources), and oblige themselves to help others, regardless of what’s going on in their lives. But Black women are not superwomen, even if they do a damn good job of faking it.

Consider it “survival mode” — and Black women have been living in this high-stress state for far too long, according to Tashia P. Chambers, a licensed clinical social worker based in Los Angeles. “A lot of my work as a therapist is shifting clients’ conditioning from survival to that which allows space and opportunity to thrive,” says Chambers. “We don’t have to be so strong. We don’t have to please others at the expense of ourselves. We don’t have to save everybody. We don’t have to always sacrifice.”

But more often than not, Black women do all of these things on a daily basis, and their health likely pays the price. “The legacy of strength in the face of stress among African American women might have something to do with the current health disparities that African American women face,” writes Cheryl L. Woods-Giscombé, Ph.D., R.N., author of the “Superwoman Schema” research.

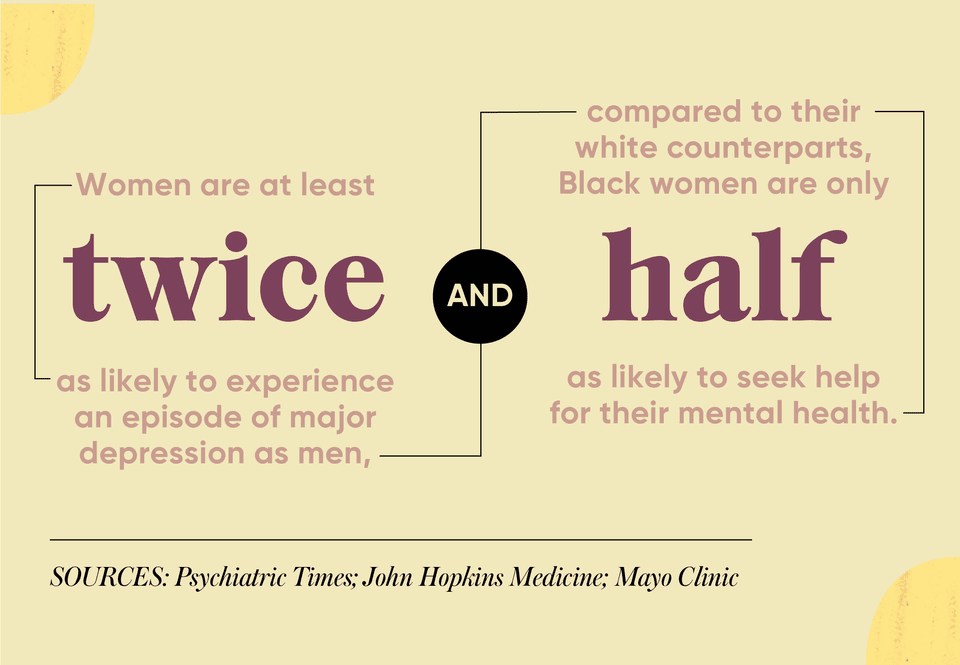

The data backs this up: Not only are Black Americans 20 percent more likely than the rest of the population to develop serious mental health issues, but they’re also more likely to be exposed to factors, such as racism, historical trauma from the medical community, exclusion from health resources, food insecurity, poverty, and subjection to crime, among other things, that increase their risk for developing a mental health condition. Research even shows that Black adults are more likely to report persistent symptoms of emotional distress (think: sadness and hopelessness) than their white counterparts, but only one in three Black Americans who need mental health care ultimately receives it.

These issues are only compounded for Black women. Women between the ages of 18 to 82 years old who identified as a strong Black woman and also agreed with self-silencing (think: repressing feelings) experienced greater depressive symptoms, according to a 2018 study in the journal Sex Roles. What’s more, a 2015 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that, during a four-year period, Black women only used mental health services at a rate of 10.3 percent compared to 21.5 percent of white women.

All of that said, research dating as far back as 2009 shows that the stigma that many millennial Black women grew up with around therapy and seeking mental health help is fading. “There’s a move toward [Black] women recognizing their needs more,” explains Amanda Jurist, a board-certified licensed clinical social worker who specializes in child, adolescent, family, and adult psychotherapy.

“I believe a part of it is that we are sick of being traumatized — mostly by grandmama and other elder family members — and want better for ourselves and future generations,” says Chambers.

Tashia P. Chambers, L.C.S.W.

This work is ancestral. We can break the cycle and create a newer healthier culture for our people when we intentionally care for our mental health.

While it’s possible to do the work to ease the mental health burdens on Black women, Jurist says that whether they can actually meet their needs of self-care is another story. Still, she says she’s happy that Black women are starting to have more of these conversations, helping to break down those false notions that there should be shame or embarrassment about having a human experience and seeking help when you need support. “We’re beginning to normalize having emotional experiences, and taking time to process that,” she says.

*Jennifer H., 46, who has battled severe depression since she was about 25, agrees. "It's only been within the last five to seven years that I've been willing to share with people that I go to therapy, and while it's still uncomfortable to say, I'm tired of carrying the weight of pretending to be okay when I am not," she says. "While going to therapy and telling people I was going to therapy didn't provide immediate relief, it has continued to allow me to embrace my authentic self — flaws and all."

It seems art is imitating life, and helping to usher in this new perspective. For example, in the 2021 Starz show Run the World, which centers on four Black 30-something women living in Harlem, there's an episode titled "My Therapist Says…" that highlights each woman's therapy session. There's also the HBO revival of In Treatment featuring Uzo Aduba as Dr. Brooke Taylor, a Black female therapist who treats a myriad of patients, including a young Black woman. In the show, Aduba's character sees a therapist, too.

Social media is also creating a supportive community for Black women to discuss mental health issues and therapy options. “It’s been a wonderful, though complicated place, that has helped to create space for voices that validate human experiences like anxious moments, depressive moments, overwhelming moments, and Black women not needing to hold everything,” says Jurist. “It can really be a great tool in normalizing that Black women don’t have to be embarrassed or ashamed about not being able to carry their load, their children’s loads, their partner’s load.”There are also a host of prominent celebrities — from Taraji P. Henson and Jada Smith to Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles to Lizzo and Mariah Carey — who are using their platforms to share their mental health stories in an effort to destigmatize the discussion and encourage others to find treatment that can help them return to their happiest self.

Yes, the stigma of therapy still exists. But, with that narrative slowly changing, it’s important to turn attention to other barriers that stand between Black women seeking the help they need. “It’s the lack of access overall and the lack of access to culturally competent care,” says Erica Martin Richards, M.D., Ph.D., chair and medical director of the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C. “There are not enough people who deliver mental health care who look like us and have our shared experiences,” says Dr. Doomes. According to a 2018 report from the American Psychological Association’s Center for Workforce Studies, African-Americans make up only 4 percent of therapists. (See: Why the U.S. Needs More Black Female Doctors)

“One of the hardest things about therapy is finding a therapist that you feel comfortable with, where you feel seen and whose work aligns with what you need and who you are,” says Hope Baptiste, 32, who has been diagnosed with an anxiety and panic disorder, depression, and ADHD. She says finding the right therapist helped her regain control of the reins of her life. “The biggest thing that turns people away from therapy is divulging vulnerable, painful, challenging parts of ourselves to someone who might not be the right fit,” she says. For Baptiste, who finally found a therapist through Open Path Therapy Collective, a non-profit nationwide network of mental health professionals, that meant unpacking the trauma of being adopted as well as being an interracial adoptee, and how these scenarios caused outsiders to pass judgment on her. “Mental health work brings up deep-rooted fears and shame,” she says. “Going to therapy and doing the internal work means facing parts of ourselves that are really hard to face.”

Not to mention, therapists aren’t necessarily jumping to help Black women deal with their issues. A small 2016 study published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior revealed that therapists were more likely to call back new potential patients who they thought were white and middle-class than those they assumed to be Black. Add to that the cost of therapy, the fact that many insurances do not adequately cover mental health treatment, and that therapists usually hold 9 to 5 hours, and the process for many Black women to seek out and get therapy, even if they’re open to receiving it, becomes that much more complicated.

Finally, Dr. Doomes notes that in therapy, there can be something called countertransference, which is when a therapist transfers their own experiences and emotions to a person in therapy. So, if you’re a Black woman who is being seen by a white therapist, for example, that “white therapist may bring into a session with a Black woman with the societal obsessions of the ‘strong Black woman,’ or the ‘angry Black woman,'” she says. “And that is in the room as they are attempting to provide therapy. It can be challenging to look at someone you were raised to believe was invincible as someone in need of mental health care?” “Black women need safe spaces to be vulnerable,” adds Dr. Doomes. “And that likely isn’t on the couch of a white male or female on the Upper East Side.”

Aside from a space that allows vulnerability, "we have to shift the culture of acceptance to the need to rest and not work more, but just rest," says Dr. Doomes. The problem: Historically, Black women have never really been afforded this opportunity.

"As enslaved people, Black women truly carried it all — carried children, birthed children in the most inhumane circumstances, worked the fields, worked in people's homes, were wet nurses, and had their own families privately and secretly to provide for," explains Jurist. And some of that historical trauma is still present. "Feelings and emotions are harder for us to access because historically there has been a message sent that there isn't space for help. That survival comes from us being able to balance and do all of these things. We are just now slowing down to have conversations to tap into our needs to move from trauma response around survival to thriving."

To do so, it’s essential to eliminate whatever is getting in the way of seeking the help you need, says Jurist. If the barrier is finding a culturally competent therapist in your likeness, Jurist suggests organizations such as Therapy for Black Girls that she says do a good job of creating an online community where it’s easy to access Black clinicians. If the barrier is financial, Jurist advises calling a clinician and talking to them about their fees, noting that many will work with you on a sliding scale, meaning they may be able to adjust the price depending on what you can afford. If the barrier is time, then try connecting digitally through teletherapy, which can help ease the time commitment. Regardless, there is still an element of luxury tied to therapy because it assumes you have that 50 minutes to step away from work or child care or whatever the obstacle for a session, notes Jurist.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of solutions, but it’s a start. And sometimes you just need someone to open the door for you. That is exactly what happened for Kanika: Through conversations with a friend who extolled the benefits of therapy, she gained the courage to go, she explains. (See: Why Is It So Hard to Make Your First Therapy Appointment?)

“Within our circle, she would speak about her experience in therapy and the revelations she was making,” says Kanika. “It felt ‘normal,’ familiar and safe. We created a space that normalized self-care in all of its forms.” And that space afforded Kanika the opportunity to work with a professional on everything from marriage counseling and the micro- and macro-aggressions she experienced at work to her feelings of being unable to protect her Black son as he entered high school in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

"Seeing a therapist has benefitted me immensely in all areas of my life," says Kanika, though she admits that a shift in her financial situation has led her to reluctantly pause therapy for now. "I gained the confidence to shed so many things that no longer served me and move along a journey toward inner peace."

FITNESS MOTIVATION

FITNESS MOTIVATION